Ruby has always been one of my favorite languages, though I’ve sometimes found it hard to express why that is. The best I’ve been able to do is this musical analogy: Whereas Python feels to me like punk rock—it’s simple, predictable, but rigid—Ruby feels like jazz. Ruby gives programmers a radical freedom to express themselves, though that comes at the cost of added complexity and can lead to programmers writing programs that don’t make immediate sense to other people.

I’ve always been aware that freedom of expression is a core value of the Ruby community. But what I didn’t appreciate is how deeply important it was to the development and popularization of Ruby in the first place. One might create a programming lanugage in pursuit of better peformance, or perhaps timesaving abstractions—the Ruby story is interesting because instead the goal was, from the very beginning, nothing more or less than the happiness of the programmer.

Yukihiro Matsumoto

Yukihiro Matsumoto, also known as “Matz,” graduated from the University of Tsukuba in 1990. Tsukuba is a small town just northeast of Tokyo, known as a center for scientific research and technological devlopment. The University of Tsukuba is particularly well-regarded for its STEM programs. Matsumoto studied Information Science, with a focus on programming languages. For a time he worked in a programming language lab run by Ikuo Nakata.

Matsumoto started working on Ruby in 1993, only a few years after graduating. He began working on Ruby because he was looking for a scripting language with features that no existing scripting language could provide. He was using Perl at the time, but felt that it was too much of a “toy language.” Python also fell short; in his own words:

I knew Python then. But I didn’t like it, because I didn’t think it was a true object-oriented language—OO features appeared to be an add-on to the language. As a language maniac and OO fan for 15 years, I really wanted a genuine object-oriented, easy-to-use scripting language. I looked for one, but couldn’t find one.1

So one way of understanding Matsumoto’s motivations in creating Ruby is that he was trying to create a better, object-oriented version of Perl.

But at other times, Matsumoto has said that his primary motivation in creating Ruby was simply to make himself and others happier. Toward the end of a Google tech talk that Matsumoto gave in 2008, he showed the following slide:

He told his audience,

I hope to see Ruby help every programmer in the world to be productive, and to enjoy programming, and to be happy. That is the primary purpose of the Ruby language.2

Matsumoto goes on to joke that he created Ruby for selfish reasons, because he was so underwhelmed by other languages that he just wanted to create something that would make him happy.

The slide epitomizes Matsumoto’s humble style. Matsumoto, it turns out, is a practicing Mormon, and I’ve wondered whether his religious commitments have any bearing on his legendary kindness. In any case, this kindness is so well known that the Ruby community has a principle known as MINASWAN, or “Matz Is Nice And So We Are Nice.” The slide must have struck the audience at Google as an unusual one—I imagine that any random slide drawn from a Google tech talk is dense with code samples and metrics showing how one engineering solution is faster or more efficient than another. Few, I suspect, come close to stating nobler goals more simply.

Ruby was influenced primarily by Perl. Perl was created by Larry Wall in the

late 1980s as a means of processing and transforming text-based reports. It

became well-known for its text processing and regular expression capabilities.

A Perl program contains many syntactic elements that would be familiar to a

Ruby programmer—there are $ signs, @ signs, and even elsifs, which I’d

always thought were one of Ruby’s less felicitous idiosyncracies. On a deeper

level, Ruby borrows much of Perl’s regular expression handling and standard

library.

But Perl was by no means the only influence on Ruby. Prior to beginning work on

Ruby, Matsumoto worked on a mail client written entirely in Emacs Lisp. The

experience taught him a lot about the inner workings of Emacs and the Lisp

language, which Matsumoto has said influenced the underlying object model of

Ruby. On top of that he added a Smalltalk-style messsage passing system which

forms the basis for any behavior relying on Ruby’s #method_missing. Matsumoto

has also claimed Ada and Eiffel as influences on Ruby.

When it came time to decide on a name for Ruby, Matsumoto and a colleague, Keiju Ishitsuka, considered several alternatives. They were looking for something that suggested Ruby’s relationship to Perl and also to shell scripting. In an instant message exchange that is well-worth reading, Ishitsuka and Matsumoto probably spend too much time thinking about the relationship between shells, clams, oysters, and pearls and get close to calling the Ruby language “Coral” or “Bisque” instead. Thankfully, they decided to go with “Ruby”, the idea being that it was, like “pearl”, the name of a valuable jewel. It also turns out that the birthstone for June is a pearl while the birthstone for July is a ruby, meaning that the name “Ruby” is another tongue-in-cheek “incremental improvement” name like C++ or C#.

Ruby Goes West

Ruby grew popular in Japan very quickly. Soon after its initial release in 1995, Matz was hired by a Japanese software consulting group called Netlab (also known as Network Applied Communication Laboratory) to work on Ruby full-time. By 2000, only five years after it was initially released, Ruby was more popular in Japan than Python. But it was only just beginning to make its way to English-speaking countries. There had been a Japanese-language mailing list for Ruby discussion since almost the very beginning of Ruby’s existence, but the English-language mailing list wasn’t started until 1998. Initially, the English-language mailing list was used by Japanese Rubyists writing in English, but this gradually changed as awareness of Ruby grew.

In 2000, Dave Thomas published Programming Ruby, the first English-language book to cover Ruby. The book became known as the “pickaxe” book for the pickaxe it featured on its cover. It introduced Ruby to many programmers in the West for the first time. Like it had in Japan, Ruby spread quickly, and by 2002 the English-language Ruby mailing list had more traffic than the original Japanese-language mailing list.

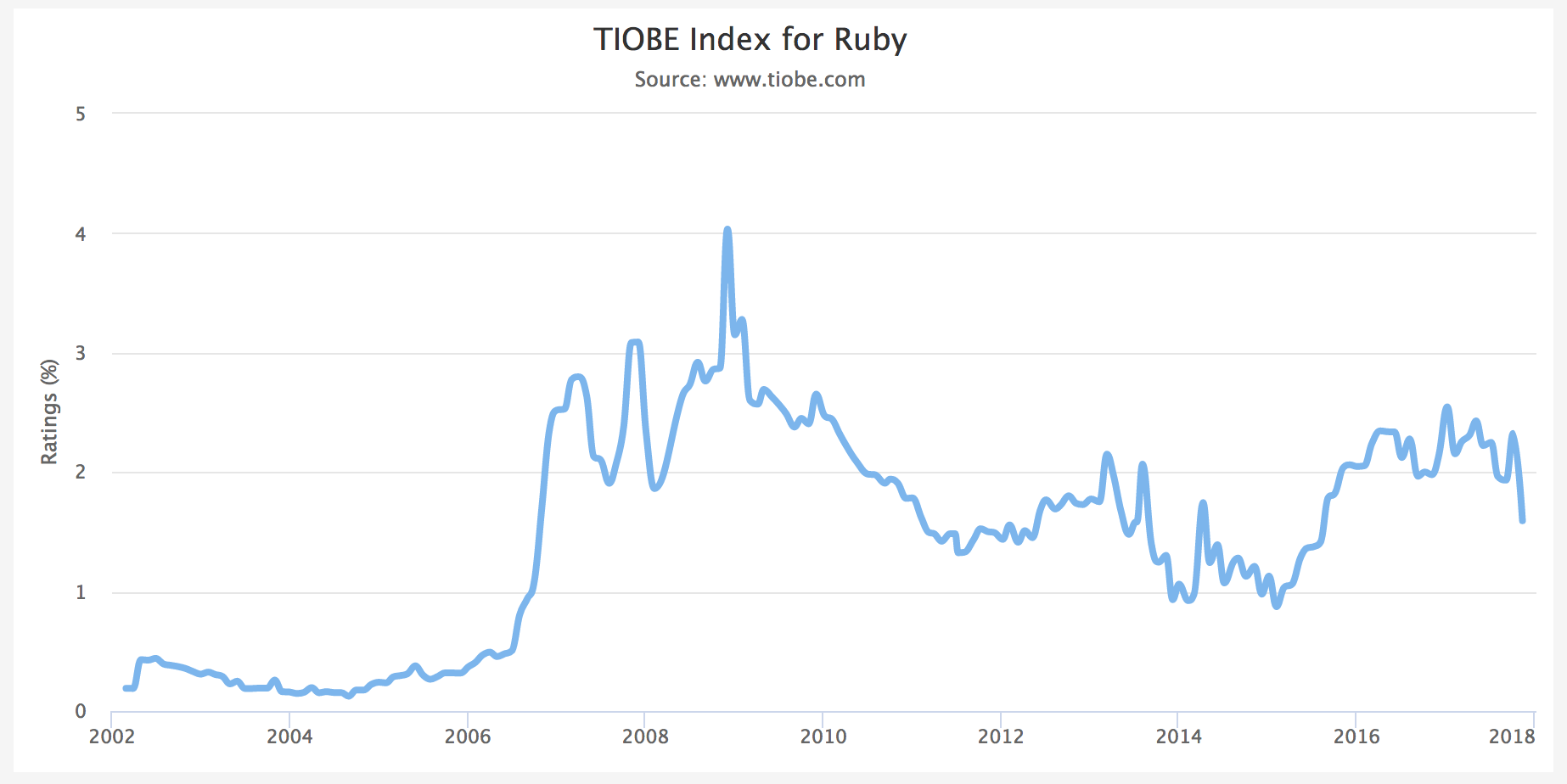

By 2005, Ruby had become more popular, but it was still not a mainstream programming language. That changed with the release of Ruby on Rails. Ruby on Rails was the “killer app” for Ruby, and it did more than any other project to popularize Ruby. After the release of Ruby on Rails, interest in Ruby shot up across the board, as measured by the TIOBE language index:

It’s sometimes joked that the only programs anybody writes in Ruby are Ruby-on-Rails web applications. That makes it sound as if Ruby on Rails completely took over the Ruby community, which is only partly true. While Ruby has certainly come to be known as that language people write Rails apps in, Rails owes as much to Ruby as Ruby owes to Rails.

The Ruby philosophy heavily informed the design and implementation of Rails. David Heinemeier Hansson, who created Rails, often talks about how his first contact with Ruby was an almost religious experience. He has said that the encounter was so transformative that it “imbued him with a calling to do missionary work in service of Matz’s creation.”3 For Hansson, Ruby’s no-shackles approach was a politically courageous rebellion against the top-down impositions made by languages like Python and Java. He appreciated that the language trusted him and empowered him to make his own judgements about how best to express his programs.

Like Matsumoto, Hansson claims that he created Rails out of a frustration with

the status quo and a desire to make things better for himself. He, like

Matsumoto, prioritized programmer happiness above all else, evaluating

additions to Rails by what he calls “The Principle of The Bigger Smile.”

Whatever made Hansson smile more was what made it into the Rails codebase.

As a result, Rails would come to include unorthodox features like the

“Inflector” class (which tries to map singular class names to plural database

table names automatically) and Rails’ Time extensions (allowing programmers

to write cute expressions like 2.days.ago). To some, these features were

truly weird, but the success of Rails is testament to the number of people who

found it made their lives much easier.

And so, while it might seem that Rails was an incidental application of Ruby that happened to become extremely popular, Rails in fact embodies many of Ruby’s core principles. Futhermore, it’s hard to see how Rails could have been built in any other language, given its dependence on Ruby’s macro-like class method calls to implement things like model associations. Some people might take the fact that so much of Ruby development revolves around Ruby on Rails as a sign of an unhealthy ecosystem, but there are good reasons that Ruby and Ruby on Rails are so intertwined.

The Future of Ruby

People seem to have an inordinate amount of interest in whether or not Ruby (and Ruby on Rails) are dying. Since as early as 2011, it seems that Stack Overflow and Quora have been full of programmers asking whether or not they should bother learning Ruby if it will no longer be around in the next few years. These concerns are not unjustified; according to the TIOBE index and to Stack Overflow trends, Ruby and Ruby on Rails have been shrinking in popularity. Though Ruby on Rails was once the hot new thing, it has since been eclipsed by hotter and newer frameworks.

One theory for why this has happened is that programmers are abandoning dynamically typed languages for statically typed ones. Analysts at TIOBE index figure that a rise in quality requirements have made runtime exceptions increasingly unacceptable. They cite TypeScript as an example of this trend—a whole new version of JavaScript was created just to ensure that client-side code could be written with the benefit of compile-time safety guarantees.

A more likely answer, I think, is just that Ruby on Rails now has many more competitors than it once did. When Rails was first introduced in 2005, there weren’t that many ways to create web applications—the main alternative was Java. Today, you can create web applications using great frameworks built for Go, JavaScript, or Python, to name only the most popular options. The web world also seems to be moving toward a more distributed architecture for applications, meaning that, rather than having one codebase responsible for everything from database access to view rendering, responsibilites are split between different components that focus on doing one thing well. Rails feels overbroad and bloated for something as focused as a JSON API that talks to a JavaScript frontend.

All that said, there are reasons to be optimistic about Ruby’s future. Both Rails and Ruby continue to be actively developed. Matsumoto and others are working hard on Ruby’s third major release, which they aim to make three times faster than the existing version of Ruby, possibly alleviating the performance concerns that have always dogged Ruby. And even if the world of web frameworks has become more diverse since 2005, that doesn’t mean that there won’t always be room for Ruby on Rails. It is now a mature tool with an enormous amount of built-in power that will always be a good choice for certain kinds of applications.

But even if Ruby and Rails go the way of the dinosaurs, one thing that seems certain to survive is the Ruby ethos of programmer happiness. Ruby has had a profound influence on the design of many new programming languages, which have adopted many of its best ideas. Other new lanuages have tried to be “more modern” interpretations of Ruby: Elixir, for example, is a version of Ruby that emphasizes the functional programming paradigm, while Crystal, which is still in development, aims to be a statically typed version of Ruby. Many programmers around the world have fallen in love with Ruby and its syntax, so we can count on its influence persisting for a long while to come.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every four weeks! Follow @TwoBitHistory on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS feed to make sure you know when a new post is out.