Lines of code longer than 80 characters drive me crazy. I appreciate that this is pedantic. I’ve seen people on the internet make good arguments for why the 80-character limit ought to be respected even on our modern Retina-display screens, but those arguments hardly justify the visceral hatred I feel for even that one protruding 81st character.

There was once a golden era in which it was basically impossible to go over the 80-character limit. The 80-character limit was a physical reality, because there was no 81st column for an 81st character to fit in. Any programmers attempting to name a function something horrendously long and awful would discover, in a moment of delicious, slow-dawning horror, that there literally isn’t room for their whole declaration.

This golden era was the era of punch card programming. By the 1960s, IBM’s

punch cards had set the standard and the standard was that punch cards had 80

columns. The 80-column standard survived into the teletype and dumb terminal

era and from there embedded itself into the nooks and crannies of our operating

systems. Today, when you launch your terminal emulator and open a new window,

odds are it will be 80 characters wide, even though we now have plenty of

screen real estate and tend to favor longer identifiers over inscrutable

nonsense like iswcntrl().

If questions on Quora are any indication, many people have trouble imagining what it must have been like to program computers using punch cards. I will admit that for a long time I also didn’t understand how punch card programming could have worked, because it struck me as awfully labor-intensive to punch all those holes. This was a misunderstanding; programmers never punched holes in cards the same way a train conductor does. They had card punch machines (also known as key punches), which allowed them to punch holes in cards using a typewriter-style keyboard. And card punches were hardly new technology—they were around as early as the 1890s.

One of the most widely used card punch machines was the IBM 029. It is perhaps the best remembered card punch today.

The IBM 029 was released in 1964 as part of IBM’s System/360 rollout. System/360 was a family of computing systems and peripherals that would go on to dominate the mainframe computing market in the late 1960s. Like many of the other System/360 machines, the 029 was big. This was an era when the distinction between computing machinery and furniture was blurry—the 029 was not something you put on a table but an entire table in itself. The 029 improved upon its predecessor, the 026, by supporting new characters like parentheses and by generally being quieter. It had cool electric blue highlights and was flat and angular whereas the 026 had a 1940s rounded, industrial look. Another of its big selling points was that it could automatically left-pad numeric fields with zeros, demonstrating that JavaScript programmers were not the first programmers too lazy to do their own left-padding.

But wait, you might say—IBM released a brand-new card punch in 1964? What about that photograph of the Unix gods at Bell Labs using teletype machines in, like, 1970? Weren’t card punching machines passé by the mid- to late-1960s? Well, it might surprise you to know that the 029 was available in IBM’s catalog until as late as 1984.1 In fact, most programmers programmed using punch cards until well into the 1970s. This doesn’t make much sense given that there were people using teletype machines during World War II. Indeed, the teletype is almost of the same vintage as the card punch. The limiting factor, it turns out, was not the availability of teletypes but the availability of computing time. What kept people from using teletypes was that teletypes assumed an interactive, “online” model of communication with the computer. Before Unix and the invention of timesharing operating systems, your interactive session with a computer would have stopped everyone else from using it, a delay potentially costing thousands of dollars. So programmers instead wrote their programs offline using card punch machines and then fed them into mainframe computers later as batch jobs. Punch cards had the added benefit of being a cheap data store in an era where cheap, reliable data storage was hard to come by. Your programs lived in stacks of cards on your shelves rather than in files on your hard drive.

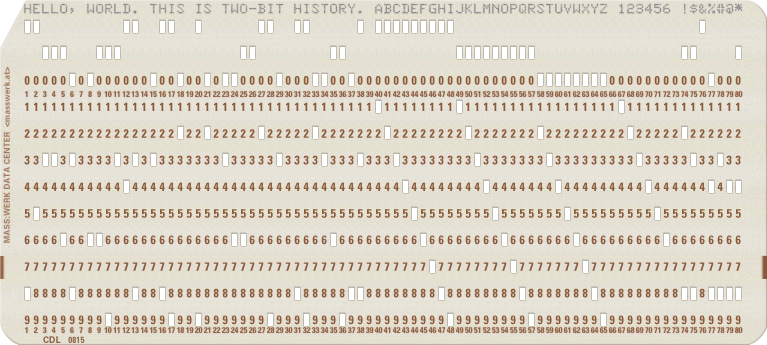

So what was it actually like using an IBM 029 card punch? That’s hard to explain without first taking a look at the cards themselves. A typical punch card had 12 rows and 80 columns. The bottom nine rows were the digit rows, numbered one through nine. These rows had the appropriate digit printed in each column. The top three rows, called the “zone” rows, consisted of two blank rows and usually a zero row. Row 12 was at the very top of the card, followed by row 11, then rows zero through nine. This somewhat confusing ordering meant that the top edge of the card was called the 12 edge while the bottom was called the nine edge. A corner of each card was usually clipped to make it easier to keep a stack of cards all turned around the right way.

When they were first invented, punch cards were meant to be punched with circular holes, but IBM eventually realized that they could fit more columns on a card if the holes were narrow rectangles. Different combinations of holes in a column represented different characters. For human convenience, card punches like the 029 would print each column’s character at the top of the card at the same time as punching the necessary holes. Digits were represented by one punched hole in the appropriate digit row. Alphabetical and symbolic characters were represented by a hole in a zone row and then a combination of one or two holes in the digit rows. The letter A, for example, was represented by a hole in the 12 zone row and another hole in the one row. This was an encoding of sorts, sometimes called the Hollerith code, after the original inventor of the punch card machine. The encoding allowed for only a relatively small character set; lowercase letters, for example, were not represented. Some clever engineer today might wonder why punch cards didn’t just use a binary encoding—after all, with 12 rows, you could encode over 4000 characters. The Hollerith code was used instead because it ensured that no more than three holes ever appeared in a single column. This preserved the structural integrity of the card. A binary encoding would have entailed so many holes that the card would have fallen apart.

Cards came in different flavors. By the 1960s, 80 columns was the standard, but those 80 columns could be used to represent different things. The basic punch card was unlabeled, but cards meant for COBOL programming, for example, divided the 80 columns into fields. On a COBOL card, the last eight columns were reserved for an identification number, which could be used to automatically sort a stack of cards if it were dropped (apparently a perennial hazard). Another column, column seven, could be used to indicate that the statement on this card was a continuation of a statement on a previous card. This meant that if you were truly desperate you could circumvent the 80-character limit, though whether a two-card statement counts as one long line or just two is unclear. FORTRAN cards were similar but had different fields. Universities often watermarked the punch cards handed out by their computing centers, while other kinds of designs were introduced for special occasions like the 1976 bicentennial.

Ultimately the cards had to be read and understood by a computer. IBM sold a System/360 peripheral called the IBM 2540 which could read up to 1000 cards per minute.2 The IBM 2540 ran electrical brushes across the surface of each card which made contact with a plate behind the cards wherever there was a hole. Once read, the System/360 family of computers represented the characters on each punch card using an 8-bit encoding called EBCDIC, which stood for Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code. EBCDIC was a proper binary encoding, but it still traced its roots back to the punch card via an earlier encoding called BCDIC, a 6-bit encoding which used the low four bits to represent a punch card’s digit rows and the high two bits to represent the zone rows. Punch card programmers would typically hand their cards to the actual computer operators, who would feed the cards into the IBM 2540 and then hand the printed results back to the programmer. The programmer usually didn’t see the computer at all.

What the programmer did see a lot of was the card punch. The 029 was not a computer, but that doesn’t mean that it wasn’t a complicated machine. The best way to understand what it was like using the 029 is to watch this instructional video made by the computing center at the University of Michigan in 1967. I’m going to do my best to summarize it here, but if you don’t watch the video you will miss out on all the wonderful clacking and whooshing.

The 029 was built around a U-shaped track that the punch cards traveled along. On the right-hand side, at the top of the U, was the card hopper, which you would typically load with a fresh stack of cards before using the machine. The IBM 029 worked primarily with 80-column cards, but the card hopper could accommodate smaller cards if needed. Your punch cards would start in the card hopper, travel along the line of the U, and then end up in the stacker, at the top of the U on the left-hand side. The cards would accumulate there in the order that you punched them.

To turn the machine on, you flipped a switch under the desk at about the height of your knees. You then pressed the “FEED” key twice to get cards loaded into the machine. The business part of the card track, the bottom of the U, was made up of three separate stations: On the right was a kind of waiting area, in the middle was the punching station, and on the left was the reading station. Pressing the “FEED” key twice loaded one card into the punching station and one card into the waiting area behind it. A column number indicator right above the punching station told you which column you were currently punching. With every keystroke, the machine would punch the requisite holes, print the appropriate character at the top of the card, and then advance the card through the punching station by one column. If you punched all 80 columns, the card would automatically be released to the reading station and a new card would be loaded into the punching station. If you wanted this to happen before you reached the 80th column, you could press the “REL” key (for “release”).

The printed characters made it easy to spot a mistake. But fixing a mistake, as the University of Michigan video warns, is not as easy as whiting out the printed character at the top of the card and writing in a new one. The holes are all that the computer will read. Nor is it as easy as backspacing one space and typing in a new character. The holes have already been punched in the column, after all, and cannot be unpunched. Punching more holes will only produce an invalid combination not associated with any character. The IBM 029 did have a backspace button that moved the punched card backward one column, but the button was placed on the face of the machine instead of on the keyboard. This was probably done to discourage its use, since backspacing was so seldom what the user actually wanted to do.

Instead, the only way to correct a mistake was scrap the incorrect card and punch a new one. This is where the reading station came in handy. Say you made a mistake in the 68th column of a card. To fix your mistake, you could carefully repunch the first 67 columns of a new card and then punch the correct character in the 68th column. Alternatively, you could release the incorrect card to the reading station, load a new card into the punching station, and hold down the “DUP” key (for duplicate) until the column number indicator reads 68. You could then correct your mistake by punching the correct character. The reading station and the “DUP” key together allowed IBM 029 operators to easily copy the contents of one card to the next. There were all sorts of reasons to do this, but correcting mistakes was the most common.

The “DUP” key allowed the 029’s operator to invoke the duplicate functionality manually. But the 029 could also duplicate automatically where necessary. This was particularly useful when punched cards were used to record data rather than programs. For example, you might be using each card to record information about a single undergraduate university student. On each card, you might have a field that contains the name of that student’s residence hall. Perhaps you find yourself entering data for all the students in one residence hall at one time. In that case, you’d want the 029 to automatically copy over the previous card’s residence hall field every time you reached the first column of the field.

Automated behavior like this could be programmed into the 029 by using the program drum. The drum sat upright in the middle of the U above the punching station. You programmed the 029 by punching holes in a card and wrapping that card around the program drum. The punched card allowed you to specify the automatic behavior you expected from the machine at each column of the card currently in the punching station. You could specify that a column should automatically be copied from the previous card, which is how an 029 operator might more quickly enter student records. You could also specify, say, that a particular field should contain numeric or alphabetic characters, or that a given field should be left blank and skipped altogether. The program drum made it much easier to punch schematized cards where certain column ranges had special meanings. There is another “advanced” instructional video produced by the University of Michigan that covers the program drum that is worth watching, provided, of course, that you have already mastered the basics.

Watching either of the University of Michigan videos today, what’s surprising is how easy the card punch is to operate. Correcting mistakes is tedious, but otherwise the machine seems to be less of an obstacle than I would have expected. Moving from one card to the next is so seamless that I can imagine COBOL or FORTRAN programmers forgetting that they are creating separate cards rather than one long continuous text file. On the other hand, it’s interesting to consider how card punches, even though they were only an input tool, probably limited how early programming languages evolved. Structured programming would eventually come along and encourage people to think of entire blocks of code as one unit, but I can see how punch card programming’s emphasis on each line made structured programming hard to conceive of. It’s no wonder that punch card programmers were not the ones that decided to enclose blocks with single curly braces entirely on their own lines. How wasteful that would have seemed!

So even though nobody programs using punch cards anymore, every programmer ought to try it at least once—if only to understand why COBOL and FORTRAN look the way they do, or how 80 characters somehow became everybody’s favorite character limit.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every four weeks! Follow @TwoBitHistory on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS feed to make sure you know when a new post is out.

-

“IBM 29 Card Punch,” IBM Archives, accessed June 23, 2018, https://www-03.ibm.com/ibm/history/exhibits/vintage/vintage_4506VV4002.html. ↩

-

IBM, IBM 2540 Component Description and Operation Procedures (Rochester, MN: IBM Product Publications, 1965), September 06, 2009, accessed June 23, 2018, http://bitsavers.informatik.uni-stuttgart.de/pdf/ibm/25xx/A21-9033-1_2540_Card_Punch_Component_Description_1965.pdf. ↩