In 1993, id Software released the first-person shooter Doom, which quickly became a phenomenon. The game is now considered one of the most influential games of all time.

A decade after Doom’s release, in 2003, journalist David Kushner published a book about id Software called Masters of Doom, which has since become the canonical account of Doom’s creation. I read Masters of Doom a few years ago and don’t remember much of it now, but there was one story in the book about lead programmer John Carmack that has stuck with me. This is a loose gloss of the story (see below for the full details), but essentially, early in the development of Doom, Carmack realized that the 3D renderer he had written for the game slowed to a crawl when trying to render certain levels. This was unacceptable, because Doom was supposed to be action-packed and frenetic. So Carmack, realizing the problem with his renderer was fundamental enough that he would need to find a better rendering algorithm, started reading research papers. He eventually implemented a technique called “binary space partitioning,” never before used in a video game, that dramatically sped up the Doom engine.

That story about Carmack applying cutting-edge academic research to video games has always impressed me. It is my explanation for why Carmack has become such a legendary figure. He deserves to be known as the archetypal genius video game programmer for all sorts of reasons, but this episode with the academic papers and the binary space partitioning is the justification I think of first.

Obviously, the story is impressive because “binary space partitioning” sounds like it would be a difficult thing to just read about and implement yourself. I’ve long assumed that what Carmack did was a clever intellectual leap, but because I’ve never understood what binary space partitioning is or how novel a technique it was when Carmack decided to use it, I’ve never known for sure. On a spectrum from Homer Simpson to Albert Einstein, how much of a genius-level move was it really for Carmack to add binary space partitioning to Doom?

I’ve also wondered where binary space partitioning first came from and how the idea found its way to Carmack. So this post is about John Carmack and Doom, but it is also about the history of a data structure: the binary space partitioning tree (or BSP tree). It turns out that the BSP tree, rather interestingly, and like so many things in computer science, has its origins in research conducted for the military.

That’s right: E1M1, the first level of Doom, was brought to you by the US Air Force.

The VSD Problem

The BSP tree is a solution to one of the thorniest problems in computer graphics. In order to render a three-dimensional scene, a renderer has to figure out, given a particular viewpoint, what can be seen and what cannot be seen. This is not especially challenging if you have lots of time, but a respectable real-time game engine needs to figure out what can be seen and what cannot be seen at least 30 times a second.

This problem is sometimes called the problem of visible surface determination. Michael Abrash, a programmer who worked with Carmack on Quake (id Software’s follow-up to Doom), wrote about the VSD problem in his famous Graphics Programming Black Book:

I want to talk about what is, in my opinion, the toughest 3-D problem of all: visible surface determination (drawing the proper surface at each pixel), and its close relative, culling (discarding non-visible polygons as quickly as possible, a way of accelerating visible surface determination). In the interests of brevity, I’ll use the abbreviation VSD to mean both visible surface determination and culling from now on.

Why do I think VSD is the toughest 3-D challenge? Although rasterization issues such as texture mapping are fascinating and important, they are tasks of relatively finite scope, and are being moved into hardware as 3-D accelerators appear; also, they only scale with increases in screen resolution, which are relatively modest.

In contrast, VSD is an open-ended problem, and there are dozens of approaches currently in use. Even more significantly, the performance of VSD, done in an unsophisticated fashion, scales directly with scene complexity, which tends to increase as a square or cube function, so this very rapidly becomes the limiting factor in rendering realistic worlds.1

Abrash was writing about the difficulty of the VSD problem in the late ’90s, years after Doom had proved that regular people wanted to be able to play graphically intensive games on their home computers. In the early ’90s, when id Software first began publishing games, the games had to be programmed to run efficiently on computers not designed to run them, computers meant for word processing, spreadsheet applications, and little else. To make this work, especially for the few 3D games that id Software published before Doom, id Software had to be creative. In these games, the design of all the levels was constrained in such a way that the VSD problem was easier to solve.

For example, in Wolfenstein 3D, the game id Software released just prior to Doom, every level is made from walls that are axis-aligned. In other words, in the Wolfenstein universe, you can have north-south walls or west-east walls, but nothing else. Walls can also only be placed at fixed intervals on a grid—all hallways are either one grid square wide, or two grid squares wide, etc., but never 2.5 grid squares wide. Though this meant that the id Software team could only design levels that all looked somewhat the same, it made Carmack’s job of writing a renderer for Wolfenstein much simpler.

The Wolfenstein renderer solved the VSD problem by “marching” rays into the virtual world from the screen. Usually a renderer that uses rays is a “raycasting” renderer—these renderers are often slow, because solving the VSD problem in a raycaster involves finding the first intersection between a ray and something in your world, which in the general case requires lots of number crunching. But in Wolfenstein, because all the walls are aligned with the grid, the only location a ray can possibly intersect a wall is at the grid lines. So all the renderer needs to do is check each of those intersection points. If the renderer starts by checking the intersection point nearest to the player’s viewpoint, then checks the next nearest, and so on, and stops when it encounters the first wall, the VSD problem has been solved in an almost trivial way. A ray is just marched forward from each pixel until it hits something, which works because the marching is so cheap in terms of CPU cycles. And actually, since all walls are the same height, it is only necessary to march a single ray for every column of pixels.

This rendering shortcut made Wolfenstein fast enough to run on underpowered home PCs in the era before dedicated graphics cards. But this approach would not work for Doom, since the id team had decided that their new game would feature novel things like diagonal walls, stairs, and ceilings of different heights. Ray marching was no longer viable, so Carmack wrote a different kind of renderer. Whereas the Wolfenstein renderer, with its ray for every column of pixels, is an “image-first” renderer, the Doom renderer is an “object-first” renderer. This means that rather than iterating through the pixels on screen and figuring out what color they should be, the Doom renderer iterates through the objects in a scene and projects each onto the screen in turn.

In an object-first renderer, one easy way to solve the VSD problem is to use a z-buffer. Each time you project an object onto the screen, for each pixel you want to draw to, you do a check. If the part of the object you want to draw is closer to the player than what was already drawn to the pixel, then you can overwrite what is there. Otherwise you have to leave the pixel as is. This approach is simple, but a z-buffer requires a lot of memory, and the renderer may still expend a lot of CPU cycles projecting level geometry that is never going to be seen by the player.

In the early 1990s, there was an additional drawback to the z-buffer approach: On IBM-compatible PCs, which used a video adapter system called VGA, writing to the output frame buffer was an expensive operation. So time spent drawing pixels that would only get overwritten later tanked the performance of your renderer.

Since writing to the frame buffer was so expensive, the ideal renderer was one that started by drawing the objects closest to the player, then the objects just beyond those objects, and so on, until every pixel on screen had been written to. At that point the renderer would know to stop, saving all the time it might have spent considering far-away objects that the player cannot see. But ordering the objects in a scene this way, from closest to farthest, is tantamount to solving the VSD problem. Once again, the question is: What can be seen by the player?

Initially, Carmack tried to solve this problem by relying on the layout of Doom’s levels. His renderer started by drawing the walls of the room currently occupied by the player, then flooded out into neighboring rooms to draw the walls in those rooms that could be seen from the current room. Provided that every room was convex, this solved the VSD issue. Rooms that were not convex could be split into convex “sectors.” You can see how this rendering technique might have looked if run at extra-slow speed in this video, where YouTuber Bisqwit demonstrates a renderer of his own that works according to the same general algorithm. This algorithm was successfully used in Duke Nukem 3D, released three years after Doom, when CPUs were more powerful. But, in 1993, running on the hardware then available, the Doom renderer that used this algorithm struggled with complicated levels—particularly when sectors were nested inside of each other, which was the only way to create something like a circular pit of stairs. A circular pit of stairs led to lots of repeated recursive descents into a sector that had already been drawn, strangling the game engine’s speed.

Around the time that the id team realized that the Doom game engine might be too slow, id Software was asked to port Wolfenstein 3D to the Super Nintendo. The Super Nintendo was even less powerful than the IBM-compatible PCs of the day, and it turned out that the ray-marching Wolfenstein renderer, simple as it was, didn’t run fast enough on the Super Nintendo hardware. So Carmack began looking for a better algorithm. It was actually for the Super Nintendo port of Wolfenstein that Carmack first researched and implemented binary space partitioning. In Wolfenstein, this was relatively straightforward because all the walls were axis-aligned; in Doom, it would be more complex. But Carmack realized that BSP trees would solve Doom’s speed problems too.

Binary Space Partitioning

Binary space partitioning makes the VSD problem easier to solve by splitting a 3D scene into parts ahead of time. For now, you just need to grasp why splitting a scene is useful: If you draw a line (really a plane in 3D) across your scene, and you know which side of the line the player or camera viewpoint is on, then you also know that nothing on the other side of the line can obstruct something on the viewpoint’s side of the line. If you repeat this process many times, you end up with a 3D scene split into many sections, which wouldn’t be an improvement on the original scene except now you know more about how different parts of the scene can obstruct each other.

The first people to write about dividing a 3D scene like this were researchers trying to establish for the US Air Force whether computer graphics were sufficiently advanced to use in flight simulators. They released their findings in a 1969 report called “Study for Applying Computer-Generated Images to Visual Simulation.” The report concluded that computer graphics could be used to train pilots, but also warned that the implementation would be complicated by the VSD problem:

One of the most significant problems that must be faced in the real-time computation of images is the priority, or hidden-line, problem. In our everyday visual perception of our surroundings, it is a problem that nature solves with trivial ease; a point of an opaque object obscures all other points that lie along the same line of sight and are more distant. In the computer, the task is formidable. The computations required to resolve priority in the general case grow exponentially with the complexity of the environment, and soon they surpass the computing load associated with finding the perspective images of the objects.2

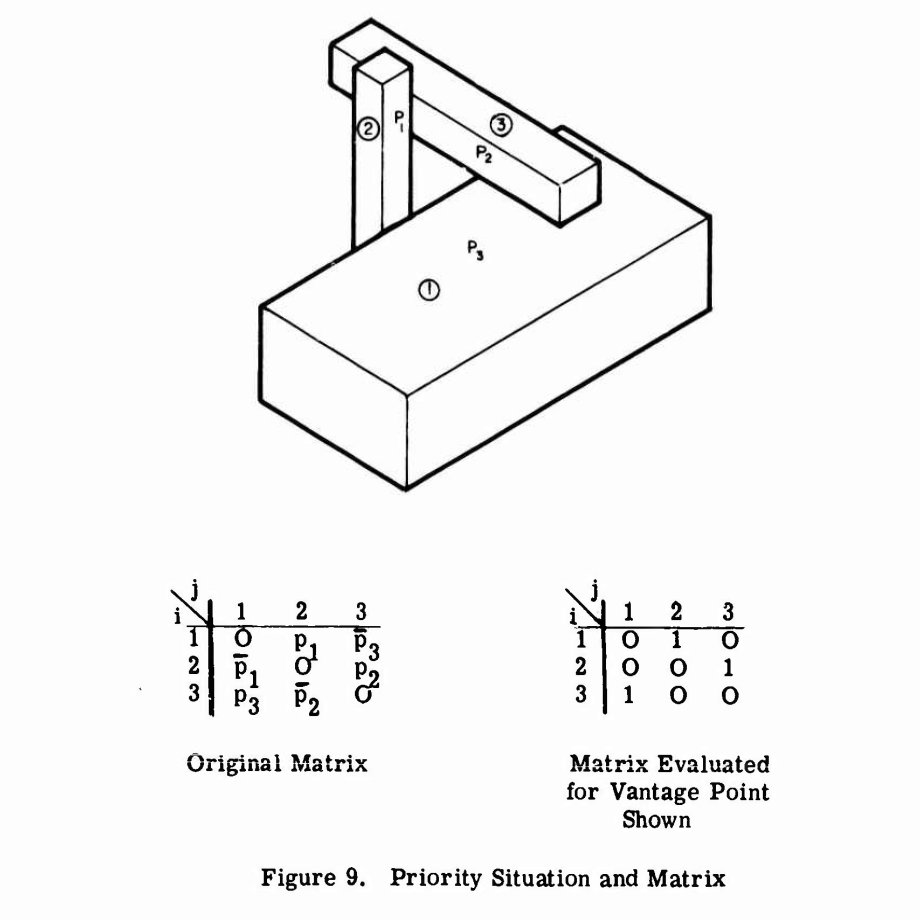

One solution these researchers mention, which according to them was earlier used in a project for NASA, is based on creating what I am going to call an “occlusion matrix.” The researchers point out that a plane dividing a scene in two can be used to resolve “any priority conflict” between objects on opposite sides of the plane. In general you might have to add these planes explicitly to your scene, but with certain kinds of geometry you can just rely on the faces of the objects you already have. They give the example in the figure below, where \(p_1\), \(p_2\), and \(p_3\) are the separating planes. If the camera viewpoint is on the forward or “true” side of one of these planes, then \(p_i\) evaluates to 1. The matrix shows the relationships between the three objects based on the three dividing planes and the location of the camera viewpoint—if object \(a_i\) obscures object \(a_j\), then entry \(a_{ij}\) in the matrix will be a 1.

The researchers propose that this matrix could be implemented in hardware and re-evaluated every frame. Basically the matrix would act as a big switch or a kind of pre-built z-buffer. When drawing a given object, no video would be output for the parts of the object when a 1 exists in the object’s column and the corresponding row object is also being drawn.

The major drawback with this matrix approach is that to represent a scene with \(n\) objects you need a matrix of size \(n^2\). So the researchers go on to explore whether it would be feasible to represent the occlusion matrix as a “priority list” instead, which would only be of size \(n\) and would establish an order in which objects should be drawn. They immediately note that for certain scenes like the one in the figure above no ordering can be made (since there is an occlusion cycle), so they spend a lot of time laying out the mathematical distinction between “proper” and “improper” scenes. Eventually they conclude that, at least for “proper” scenes—and it should be easy enough for a scene designer to avoid “improper” cases—a priority list could be generated. But they leave the list generation as an exercise for the reader. It seems the primary contribution of this 1969 study was to point out that it should be possible to use partitioning planes to order objects in a scene for rendering, at least in theory.

It was not until 1980 that a paper, titled “On Visible Surface Generation by A Priori Tree Structures,” demonstrated a concrete algorithm to accomplish this. The 1980 paper, written by Henry Fuchs, Zvi Kedem, and Bruce Naylor, introduced the BSP tree. The authors say that their novel data structure is “an alternative solution to an approach first utilized a decade ago but due to a few difficulties, not widely exploited”—here referring to the approach taken in the 1969 Air Force study.3 A BSP tree, once constructed, can easily be used to provide a priority ordering for objects in the scene.

Fuchs, Kedem, and Naylor give a pretty readable explanation of how a BSP tree works, but let me see if I can provide a less formal but more concise one.

You begin by picking one polygon in your scene and making the plane in which the polygon lies your partitioning plane. That one polygon also ends up as the root node in your tree. The remaining polygons in your scene will be on one side or the other of your root partitioning plane. The polygons on the “forward” side or in the “forward” half-space of your plane end up in the left subtree of your root node, while the polygons on the “back” side or in the “back” half-space of your plane end up in the right subtree. You then repeat this process recursively, picking a polygon from your left and right subtrees to be the new partitioning planes for their respective half-spaces, which generates further half-spaces and further sub-trees. You stop when you run out of polygons.

Say you want to render the geometry in your scene from back-to-front. (This is known as the “painter’s algorithm,” since it means that polygons further from the camera will get drawn over by polygons closer to the camera, producing a correct rendering.) To achieve this, all you have to do is an in-order traversal of the BSP tree, where the decision to render the left or right subtree of any node first is determined by whether the camera viewpoint is in either the forward or back half-space relative to the partitioning plane associated with the node. So at each node in the tree, you render all the polygons on the “far” side of the plane first, then the polygon in the partitioning plane, then all the polygons on the “near” side of the plane—”far” and “near” being relative to the camera viewpoint. This solves the VSD problem because, as we learned several paragraphs back, the polygons on the far side of the partitioning plane cannot obstruct anything on the near side.

The following diagram shows the construction and traversal of a BSP tree representing a simple 2D scene. In 2D, the partitioning planes are instead partitioning lines, but the basic idea is the same in a more complicated 3D scene.

The really neat thing about a BSP tree, which Fuchs, Kedem, and Naylor stress several times, is that it only has to be constructed once. This is somewhat surprising, but the same BSP tree can be used to render a scene no matter where the camera viewpoint is. The BSP tree remains valid as long as the polygons in the scene don’t move. This is why the BSP tree is so useful for real-time rendering—all the hard work that goes into constructing the tree can be done beforehand rather than during rendering.

One issue that Fuchs, Kedem, and Naylor say needs further exploration is the question of what makes a “good” BSP tree. The quality of your BSP tree will depend on which polygons you decide to use to establish your partitioning planes. I skipped over this earlier, but if you partition using a plane that intersects other polygons, then in order for the BSP algorithm to work, you have to split the intersected polygons in two, so that one part can go in one half-space and the other part in the other half-space. If this happens a lot, then building a BSP tree will dramatically increase the number of polygons in your scene.

Bruce Naylor, one of the authors of the 1980 paper, would later write about this problem in his 1993 paper, “Constructing Good Partitioning Trees.” According to John Romero, one of Carmack’s fellow id Software co-founders, this paper was one of the papers that Carmack read when he was trying to implement BSP trees in Doom.4

BSP Trees in Doom

Remember that, in his first draft of the Doom renderer, Carmack had been trying to establish a rendering order for level geometry by “flooding” the renderer out from the player’s current room into neighboring rooms. BSP trees were a better way to establish this ordering because they avoided the issue where the renderer found itself visiting the same room (or sector) multiple times, wasting CPU cycles.

“Adding BSP trees to Doom” meant, in practice, adding a BSP tree generator to the Doom level editor. When a level in Doom was complete, a BSP tree was generated from the level geometry. According to Fabien Sanglard, the generation process could take as long as eight seconds for a single level and 11 minutes for all the levels in the original Doom.5 The generation process was lengthy in part because Carmack’s BSP generation algorithm tries to search for a “good” BSP tree using various heuristics. An eight-second delay would have been unforgivable at runtime, but it was not long to wait when done offline, especially considering the performance gains the BSP trees brought to the renderer. The generated BSP tree for a single level would have then ended up as part of the level data loaded into the game when it starts.

Carmack put a spin on the BSP tree algorithm outlined in the 1980 paper, because once Doom is started and the BSP tree for the current level is read into memory, the renderer uses the BSP tree to draw objects front-to-back rather than back-to-front. In the 1980 paper, Fuchs, Kedem, and Naylor show how a BSP tree can be used to implement the back-to-front painter’s algorithm, but the painter’s algorithm involves a lot of over-drawing that would have been expensive on an IBM-compatible PC. So the Doom renderer instead starts with the geometry closer to the player, draws that first, then draws the geometry farther away. This reverse ordering is easy to achieve using a BSP tree, since you can just make the opposite traversal decision at each node in the tree. To ensure that the farther-away geometry is not drawn over the closer geometry, the Doom renderer uses a kind of implicit z-buffer that provides much of the benefit of a z-buffer with a much smaller memory footprint. There is one array that keeps track of occlusion in the horizontal dimension, and another two arrays that keep track of occlusion in the vertical dimension from the top and bottom of the screen. The Doom renderer can get away with not using an actual z-buffer because Doom is not technically a fully 3D game. The cheaper data structures work because certain things never appear in Doom: The horizontal occlusion array works because there are no sloping walls, and the vertical occlusion arrays work because no walls have, say, two windows, one above the other.

The only other tricky issue left is how to incorporate Doom’s moving characters into the static level geometry drawn with the aid of the BSP tree. The enemies in Doom cannot be a part of the BSP tree because they move; the BSP tree only works for geometry that never moves. So the Doom renderer draws the static level geometry first, keeping track of the segments of the screen that were drawn to (with yet another memory-efficient data structure). It then draws the enemies in back-to-front order, clipping them against the segments of the screen that occlude them. This process is not as optimal as rendering using the BSP tree, but because there are usually fewer enemies visible than there is level geometry in a level, speed isn’t as much of an issue here.

Using BSP trees in Doom was a major win. Obviously it is pretty neat that Carmack was able to figure out that BSP trees were the perfect solution to his problem. But was it a genius-level move?

In his excellent book about the Doom game engine, Fabien Sanglard quotes John Romero saying that Bruce Naylor’s paper, “Constructing Good Partitioning Trees,” was mostly about using BSP trees to cull backfaces from 3D models.6 According to Romero, Carmack thought the algorithm could still be useful for Doom, so he went ahead and implemented it. This description is quite flattering to Carmack—it implies he saw that BSP trees could be useful for real-time video games when other people were still using the technique to render static scenes. There is a similarly flattering story in Masters of Doom: Kushner suggests that Carmack read Naylor’s paper and asked himself, “what if you could use a BSP to create not just one 3D image but an entire virtual world?”7

This framing ignores the history of the BSP tree. When those US Air Force researchers first realized that partitioning a scene might help speed up rendering, they were interested in speeding up real-time rendering, because they were, after all, trying to create a flight simulator. The flight simulator example comes up again in the 1980 BSP paper. Fuchs, Kedem, and Naylor talk about how a BSP tree would be useful in a flight simulator that pilots use to practice landing at the same airport over and over again. Since the airport geometry never changes, the BSP tree can be generated just once. Clearly what they have in mind is a real-time simulation. In the introduction to their paper, they even motivate their research by talking about how real-time graphics systems must be able to create an image in at least 1/30th of a second.

So Carmack was not the first person to think of using BSP trees in a real-time graphics simulation. Of course, it’s one thing to anticipate that BSP trees might be used this way and another thing to actually do it. But even in the implementation Carmack may have had more guidance than is commonly assumed. The Wikipedia page about BSP trees, at least as of this writing, suggests that Carmack consulted a 1991 paper by Chen and Gordon as well as a 1990 textbook called Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice. Though no citation is provided for this claim, it is probably true. The 1991 Chen and Gordon paper outlines a front-to-back rendering approach using BSP trees that is basically the same approach taken by Doom, right down to what I’ve called the “implicit z-buffer” data structure that prevents farther polygons being drawn over nearer polygons. The textbook provides a great overview of BSP trees and some pseudocode both for building a tree and for displaying one. (I’ve been able to skim through the 1990 edition thanks to my wonderful university library.) Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice is a classic text in computer graphics, so Carmack might well have owned it.

Still, Carmack found himself faced with a novel problem—”How can we make a first-person shooter run on a computer with a CPU that can’t even do floating-point operations?”—did his research, and proved that BSP trees are a useful data structure for real-time video games. I still think that is an impressive feat, even if the BSP tree had first been invented a decade prior and was pretty well theorized by the time Carmack read about it. Perhaps the accomplishment that we should really celebrate is the Doom game engine as a whole, which is a seriously nifty piece of work. I’ve mentioned it once already, but Fabien Sanglard’s book about the Doom game engine (Game Engine Black Book: DOOM) is an excellent overview of all the different clever components of the game engine and how they fit together. We shouldn’t forget that the VSD problem was just one of many problems that Carmack had to solve to make the Doom engine work. That he was able, on top of everything else, to read about and implement a complicated data structure unknown to most programmers speaks volumes about his technical expertise and his drive to perfect his craft.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every four weeks! Follow @TwoBitHistory on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS feed to make sure you know when a new post is out.

Previously on TwoBitHistory…

I've wanted to learn more about GNU Readline for a while, so I thought I'd turn that into a new blog post. Includes a few fun facts from an email exchange with Chet Ramey, who maintains Readline (and Bash):https://t.co/wnXeuyjgMx

— TwoBitHistory (@TwoBitHistory) August 22, 2019

-

Michael Abrash, “Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book,” James Gregory, accessed November 6, 2019, http://www.jagregory.com/abrash-black-book/#chapter-64-quakes-visible-surface-determination. ↩

-

R. Schumacher, B. Brand, M. Gilliland, W. Sharp, “Study for Applying Computer-Generated Images to Visual Simulation,” Air Force Human Resources Laboratory, December 1969, accessed on November 6, 2019, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/700375.pdf. ↩

-

Henry Fuchs, Zvi Kedem, Bruce Naylor, “On Visible Surface Generation By A Priori Tree Structures,” ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, July 1980. ↩

-

Fabien Sanglard, Game Engine Black Book: DOOM (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 200. ↩

-

Sanglard, 206. ↩

-

Sanglard, 200. ↩

-

David Kushner, Masters of Doom (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2004), 142. ↩