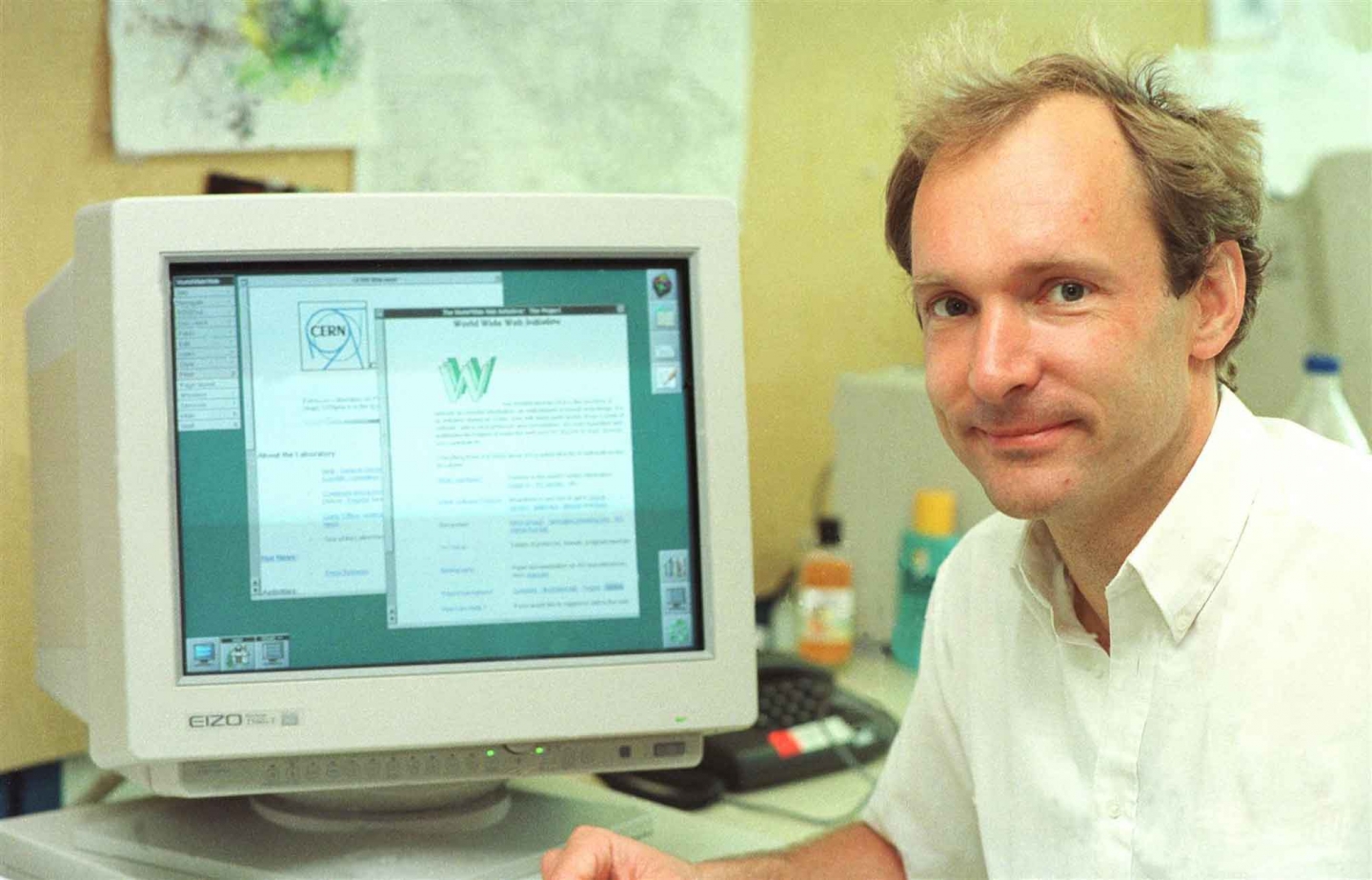

The miraculous thing about Tim Berners-Lee is that he was the perfect person for the job.

In 1989, when Berners-Lee first proposed the idea that would become the World Wide Web, exciting things were happening in the realm of computing. A new set of standards called TCP/IP were allowing previously isolated computer networks to talk to each other. These standards had become popular, particularly in the American scientific community. By 1989, TCP/IP was also just starting to be adopted by commercial service providers like CompuServe.

Meanwhile, an annual conference had recently been established to discuss a promising new avenue of computing research: hypertext. First conceived of in the 1960s, hypertext found itself back in the spotlight after Apple released a program for the Macintosh in 1987 called HyperCard. HyperCard was a kind of simplified software development environment that allowed even the least savvy Mac user to assemble an interactive application out of a “stack” of interlinked cards. Though the cards did not contain text body hyperlinks as we think of them today, a card could contain buttons that, when clicked, navigated to other cards. HyperCard was tremendously successful and even beloved by many, so much so that last year it was recreated by a fan. HyperCard’s success inspired new interest in hypertext, which some thought would supplant the printed word as the medium of the future. Hypertext, according to a book published about it at the time, was going to “produce effects on our culture, particularly on our literature, education, criticism, and scholarship just as radical as those produced by Gutenberg’s movable type.”1

The one major problem was that, in 1989, all existing hypertext systems were closed systems. Commercial applications of hypertext technology involved converting complex documentation into hypertext form and then shipping it on a floppy disk. Users could navigate the documentation more easily than if it were printed in a book, but they could not follow links to documents not already stored on the floppy disk. Some people, like Ted Nelson, who first coined the term “hypertext” in the 1960s, were searching desperately for a way to open up hypertext systems by making them work across a network—but these efforts were making little progress. It took Berners-Lee, whose personal interests and professional experiences put all the jigsaw pieces in front of him, to marry the internet and hypertext together.

ENQUIRE, Printers, and RPC

Berners-Lee had been fascinated by the promise of something like hypertext since well before HyperCard. As a child, he had talked with his father (both his parents were mathematicians and programmers) about how much better it would be if computers, rather than modeling the world in rigid hierarchies, modeled the world as a series of loose associations, the way human beings do.2 In 1980, four years after graduating from Oxford University with a degree in physics, he went to work at CERN, the particle physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland. CERN, as Berners-Lee describes it in his book about the creation of the web, had an institutional culture bordering on the anarchic.3 Ten thousand or so people were nominally a part of CERN, but only half were actually in Geneva at any given time. There were only 3000 actual, salaried employees; the rest were contractors or itinerant academics. As a contractor himself, Berners-Lee saw that one of the biggest challenges he faced was simply understanding, amid the barrage of arrivals and departures, how people and projects related to one another.

When the weather was nice, Berners-Lee and his coworkers swapped ideas while eating lunch outside, where bucolic vineyards climbed the slopes around them.4 In the evenings and during his time off, Berners-Lee worked on a program he called ENQUIRE. ENQUIRE was his attempt to map out the tangle of interconnections at CERN and was basically the first iteration of what would become the web. It used hypertext to capture the relationships that human beings would otherwise most naturally represent on a piece of paper as a set of circles and arrows. Users could make and follow links between documents, people, and concepts. The links were all of a certain type, so that, for example, the “Vacuum Control System” concept could have an “includes” relationship with the “Vacuum Equipment Modules” concept and a “described-by” relationship with a document named Controle du System a Vide du Booster. Berners-Lee named his program after a Victorian-era domestic encyclopedia and etiquette guide called Enquire Within Upon Everything, a title he liked because it evoked a magical portal to a world full of information.5 Berners-Lee found that ENQUIRE did a pretty good job of living up to its namesake and suited the chaotic, dynamic systems at CERN. But his contract with CERN would end before he had an opportunity to sell other people at CERN on its usefulness. On his way out the door, Berners-Lee handed the program to his manager on a floppy disk, but the disk was later lost.6 (ENQUIRE’s manual, however, is still available.)

ENQUIRE did not work across a computer network, so like the hypertext systems that emerged later in the 1980s, it was a closed system. It is nonetheless to Berners-Lee’s credit that he was exploring the possibilities of hypertext at such an early stage. For ENQUIRE to transform into the World Wide Web, Berners-Lee still needed to incorporate two more key technologies.

The first of these was a markup language. Serendipitously, the very next thing Berners-Lee did after CERN was go work for his friend, John Poole, on printer software. John Poole ran a company called Image Computer Systems that was trying to make smarter printers by incorporating a microprocessor. Berners-Lee helped to write, among other things, a new markup language used to prepare documents for the printer.7 SGML, the markup language that Berners-Lee would later base HTML on—HTML was in fact meant to be only a particular application or “tag set” of SGML—was first standardized in a draft specification released in 1980. So it’s possible that, while Berners-Lee was at Image Computer Systems, he worked with SGML. Even if he did not, the experience would certainly have taught him a lot about the challenges inherent in trying to render marked up text on a page, whether physical or digital.

In 1983, Berners-Lee decided he wanted to go back to working at CERN. He applied for a fellowship and moved back to Switzerland in 1984, where he joined CERN’s Electronics and Computing for Physics division. One of his first assignments was to develop an RPC (remote procedure call) protocol that would allow one CERN computer to call a function stored on another CERN computer. This might have been relatively straightforward except for the fact that CERN computers weren’t all on the same network. CERN had only grown more complex while Berners-Lee had been away and CERN employees, accustomed to making their own choices about technology, now used a range of computers and operating systems from IBM, DEC, and Control Data. Consequently, there was no single set of networking standards that all CERN computers understood. So Berners-Lee ensured that his RPC system supported multiple networking protocols. In particular, he made sure to support the TCP/IP protocol suite, which at that time was championed only by CERN’s Unix crowd but which Berners-Lee thought had great potential.8 That was when, as Berners-Lee writes, “the Internet came into my life.”9

The internet was the second key technology that enabled the web. Early in his second stint at CERN, Berners-Lee had made some desultory attempts to rewrite ENQUIRE, because he saw that the need for a program like it still existed at CERN.10 But the closed nature of ENQUIRE was too limiting. Berners-Lee began to wonder if he could combine ENQUIRE with the communication schemes he had developed for the RPC project. A networked version of ENQUIRE, relying on the increasingly popular TCP/IP standards, would allow researchers at CERN to link not only to documents on their own computers but also to documents on everyone else’s computers. At that point, all the pieces were in place. Berners-Lee told his manager, Mike Sendall, about his ideas. Sendall told him to write a proposal. And so, in 1989, Berners-Lee did.

HyperText : Text

Aware that CERN was unlikely to support a research project with no clear purpose, Berners-Lee pitched his idea as the documentation system CERN desperately lacked. With the Large Hadron Collider project just over the horizon—today, the LHC is the largest machine on the planet—CERN needed a better way to record and organize information. The software he was proposing, tentatively called the information “mesh,” would unify the many existing documentation systems at CERN into one easily navigated, remotely accessible body of hypertext. Importantly, his new system would not impose any kind of artificial hierarchy on the data being stored. In an interesting echo of Edgar F. Codd, who ten years earlier demonstrated the many advantages of the relational database model over the prevailing hierarchical models, Berners-Lee warns against letting a hierarchical method of storage put undue constraints on the information stored. Instead, users should be able to make links between nodes in the structure arbitrarily.

Berners-Lee’s original proposal is light on technical details and is almost a philosophical statement rather than a technical plan. There is no mention of markup languages or even of anything like HTTP, though Berners-Lee does say that an important part of the project will be defining an interface between clients and servers. The closest he gets to describing how his system will work in practice is when he asks his readers to imagine “the references in this document, all being associated with the network address of the thing to which they referred, so that while reading this document you could skip to them with a click of the mouse.” Reading the proposal today, it’s obvious to us what Berners-Lee is describing—that’s the web! But, in 1989, it would have been hard to grasp what this meta-documentation system was all about. Sendall supposedly wrote on his copy of the proposal that it was “vague but exciting.”11

Perhaps the most intriguing thing about the proposal is that, at least in 1989, Berners-Lee seems to have thought that he would be making a network-enabled ENQUIRE. The diagram he includes on the first page of his proposal shows nodes of several different kinds—there are people, concepts, documents, and software programs—connected according to a fixed set of relationships. ENQUIRE certainly worked that way; you had to tell it how things were related. Nodes and links were typed. But the web would not end up with typed links at all. ENQUIRE’s typed links and nodes lent themselves to interesting analysis, since you could hypothetically ask, for example, “How many people work in the Electronics and Computing for Physics division at CERN?” Answering questions like that would not be possible on the web. A decade later, Berners-Lee and hundreds of others would try to bring typing back by encouraging everyone to use semantic web technologies, with only mixed success. It’s fascinating to know that the web, at least as originally conceived, was supposed to be a semantic web all along.

Berners-Lee sent his proposal around to a few people at CERN, but it was, for the most part, politely ignored. A year later, Berners-Lee, more convinced than ever that he was on to something, worked with CERN veteran Robert Cailliau to rewrite his original proposal in more concrete terms.12 The 1990 proposal focuses on the resources that would be required to build a working prototype of what Berners-Lee was now calling “WorldWideWeb.” It also specifies that the project would involve creating, among other things, a standard protocol for retrieving documents, a standard format for representing documents, and a program that would allow users to view retrieved text documents and possibly graphics. This second proposal allowed Berners-Lee to pull together a small team and start creating the web.

The first thing that Berners-Lee worked on was a client. Berners-Lee’s manager,

Mike Sendall, had just allowed him to purchase a NeXTSTEP workstation. NeXTSTEP

was a new operating system produced by NeXT, the company that Steve Jobs

founded after being ousted from Apple. Berners-Lee had decided that the

NeXTSTEP system, known for its powerful and easy-to-use software development

framework, would make developing the “browser” program straightforward.13

Indeed, the framework, written in Objective-C and leveraging the latest new

programming paradigm (something called “object-oriented programming”), made it

as easy as creating a new subclass of the existing Text class called

HyperText. Other classes Berners-Lee wrote had the prefix HT, for

hypertext, because prefixing class names was a convention when using NeXTSTEP’s

application framework. If this seems familiar to anyone, that’s because NeXT

eventually got bought by Apple. The AppKit framework that iOS and Mac

developers know so well today is only the modern incarnation of the framework

Berners-Lee used to build the first web browser. Berners-Lee’s browser,

WorldWideWeb.app, even had an application

delegate.

The other piece of software that Berners-Lee had to write was a basic HTTP

server. That code would eventually become known as CERN HTTPd. The original

version ran on NeXT systems and on an operating system called VAX/VMS,

developed by Digital Equipment Corporation and popular among some people at

CERN. The original version fit inside one file, named

daemon.c,

which is well worth reading through. By default, the first HTTP server ran on

port 2784 and supported only GET requests and another kind of request called

FIND. It implemented the original HTTP

specification.

Soon enough, Berners-Lee had a client and a server talking to each other using HTTP. But the web browser he had built only ran on NeXT machines, which would have a long legacy in computing but which were not, in fact, all that popular. This bothered Berners-Lee, because the whole point of having a world-wide web was that it would be universal. A web browser that only ran on one system did not do a good job of demonstrating the web’s potential. So on the advice of another CERN employee, Ben Segal, Berners-Lee hired an intern named Nicola Pellow to create what they called a “line-mode” browser.14 The line-mode browser would be text-only, making it easy to port to lots of different systems. Few people remember the line-mode browser now, but many more people first encountered the web via the line-mode browser than via Berners-Lee’s original NeXT browser. The cool thing about the line-mode browser is that CERN has recently created an emulation of it, so if you’re idea of fun involves browsing the web like it’s 1991, this is something you can do.

The Web Goes Public

Berners-Lee first told people outside of CERN about the web when he described it in a post to the alt.hypertext newsgroup made in August of 1991. He was responding to a question somebody else had asked about whether anyone was working on a hypertext system that could retrieve information from “heterogeneous” sources. In the post, Berners-Lee lays out the work that had been done so far on the “WorldWideWeb” project and invites anyone interested in seeing the code to email him.

Later that year, in September, the web spread outside of Europe to the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. From there it spread to other research centers around the world. Other people began making their own web browsers for different operating systems and some of these web browsers were dramatic improvements on Berners-Lee’s original browser. In 1993, a team of young graduate students at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications in Illinois created Mosaic, which among other achievements was the first browser to display images inline instead of in a separate window. Mosaic was so easy to install and use that it kicked off a massive boom in the popularity of the web and effectively ushered in the internet age.

By the time Mosaic launched, the web had long ceased to be under Berners-Lee’s sole control. Other people would have greater influence over its evolution and growth in the years to come. But the web would, of course, always be remembered as Berners-Lee’s invention.

Could anyone else have invented the web? As is sometimes the case with new technologies, in 1989, the web—or at least something like it—seems to have been almost inevitable. Interest in hypertext was growing even as TCP/IP made it easier for different computer systems to talk to each other. Questions like the one asked on the alt.hypertext newsgroup about hypertext connecting “heterogeneous” systems show that other people were beginning to see the potential of such a system. Then again, people like Ted Nelson spent years trying to create a universal hypertext system without getting anywhere. Berners-Lee, fortunate enough to have worked with, in short order, hypertext systems, markup languages, and RPC protocols, was uniquely situated to bring those strands together. Without Berners-Lee, a “web” may eventually have emerged, but it might not have happened for several more years and it might not have resembled the free and open web that Berners-Lee gave us.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every four weeks! Follow @TwoBitHistory on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS feed to make sure you know when a new post is out.

-

Coover, Robert. “The End of Books.” The New York Times, June 21, 1992. Accessed June 2, 2018, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/98/09/27/specials/coover-end.html?pagewanted=all. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, Tim, and Mark Fischetti. Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web. (Harper Business, 2000), 3. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 9. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 1. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 11. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 12. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 19. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 15. ↩

-

“Tim Berners-Lee’s Proposal”. CERN, accessed June 10, 2018, http://info.cern.ch/Proposal.html. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 26. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 23. ↩

-

Berners-Lee, 29. ↩